This post first appeared on DZone Agile Spotlight. Its original title was “What is an Agile Retrospective” and was entered as part of the DZone bounty competition.

The first time that a lot of teams do (and what my team did when they had their retrospectives after they tried to implement Scrum or any agile process) is try to answer the following questions:

- What went well during the sprint?

- What didn’t go well?

- What can we do to improve?

We would go around the room. Each person answering the question if they wanted to. To mix it up, the manager would elicit responses, note the responses down, and then move on. The whole process took about 15-30 minutes at most and was completely USELESS!

What we did then was go by the letter of what a retrospective was, not by what its intent was.

So, What Really is an Agile Retrospective?

The retrospective is a time to reflect on the past work that has been done, and through self-assessment, determine how things went and how they can be improved. The above 3 questions may always be asked (not necessarily in the one sitting), but it is why they are asked that is as important as to how they are asked to get the most benefit from them. The goal of the retrospective is to have an action plan in place to try to improve productivity in the next iteration. I say “try” because the action plan is an experiment. Through the implementation of it in the next iteration do we determine whether or not the action plan is successful.

What Went Well?

Part of a retrospective is to look at what went well during a sprint. This serves 2 purposes:

- The first is to celebrate your success. No matter how large or small, you did something good and it should be acknowledged.

- The second is to see if this success can be replicated in other areas. Also, can it be sustained?

I recently completed a Scrum project. Now, we are a BAU (Business As Usual) team, where we mainly take care of systems rather than development, but during a recent project, it was decided to use Scrum. It was the first Scrum project for this team. For the final retrospective, one of the things I wanted the team to reflect on was, what practice could the team bring back from the Scrum project into their BAU work?

What Didn’t Go So Well?

This means “to acknowledge one’s own mistake and pledge improvement.”

One portion of the retrospective is a bit like this. When done properly, Agile uncovers problems. Problems may be small, problems may be large, but part of the retrospective is to acknowledge those problems and find ways to resolve them.

In western culture, even though it isn’t really said, mistakes are seen as a failure. They are seen as bad. So, they either get ignored, stigmatized (through blame and ridicule), or worked around. Very rarely are they directly addressed, and only then is it done so begrudgingly. Yes, all systems have problems, but it’s how you deal with those problems that is important.

One method I like to bring up to help answer the question of what didn’t go so well is to spend about 10 minutes letting the team throw out anything they didn’t like during the sprint. One example could be that planning didn’t go so well. Another could be that the sprint felt hectic. There were too many interruptions. The deployment failed. Tests failed. Anything and everything are fair game.

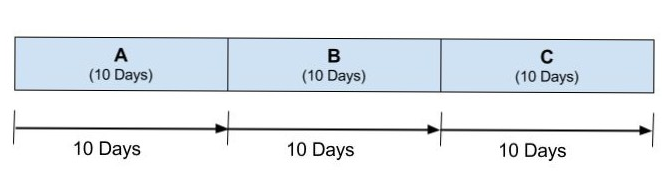

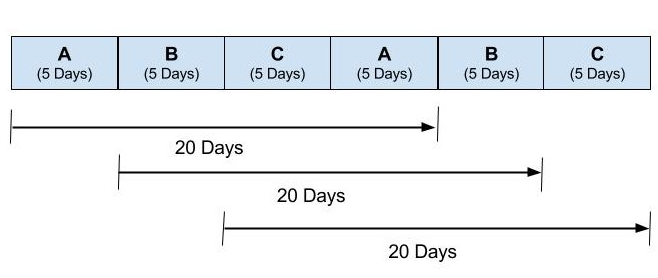

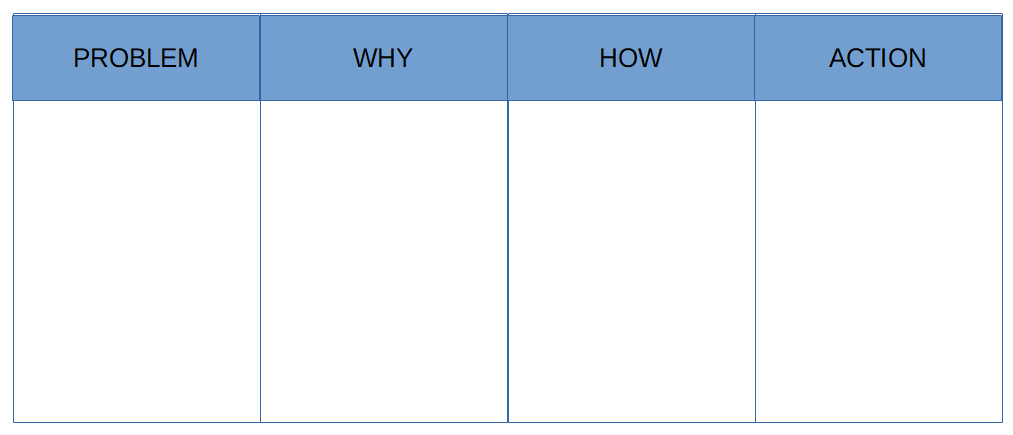

The next thing I like to do is have the team prioritize the top 3-5 problems and then explore what the root cause was. Based on that root cause, we brainstorm what can be done to try and determine a fix. And finally, one of the important results of the retrospective, we map out an action plan to alleviate the issue. I only focus on 3-5 problems and make sure that they are in distinctly separate segments of the development cycle simply because focusing on any more than that starts to become too much for the team to handle. You will also find that several problems have a common root cause.

For the action plan, there must be at least 1 action that needs to be done in the next sprint, but no more than 3. Any more than that, and again it is too much for the team to handle.

What Can be Improved?

The final question asked is to try to look at what you did during the sprint and see if there is a better way to do it. Improvements can be in the form of automation of tasks, or trying a different method or a different development language. It can also be as simple as explaining something a little better.

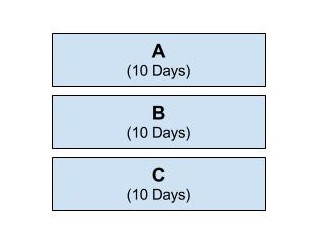

For improvements, I like to use the lean methods of eliminating waste where waste is:

- Defect

- Overproduction

- Waiting

- Non-utilized talent

- Transportation

- Inventory

- Motion

- Extra Processes

If a suggested improvement actually increases one of these wastes, it really needs to be justified.

Other Things to be Taken Into Account

An agile retrospective can take other considerations into account that help improve productivity. These can be the level of happiness of the team. A happy team is a productive team. The amount of learning the team has made during the last iteration is one example to look at the productivity level. There are many methods to do a retrospective. I’ll include some resources at the end of this article.

Rules

Within Scrum, a retrospective should take no more than 3 hours for a 1-month sprint. For shorter sprints, the time allocated should be less. For example, for 2-week sprints, I set the retrospectives to 1 hour 30 minutes maximum. Now, this is specifically for Scrum. For other agile methods, these rules may not apply.

Personally, I have two other mandatory rules:

- No blaming people. This isn’t a witch hunt. We’re all trying to solve problems and not point fingers.

- No excuses. I don’t care if you had to spend 2 days on a production problem and couldn’t do your work. What can we do to prevent the production problem from interfering again?

The final optional rule is:

- No one gets a doughnut until they speak.

This brings me to the final thing that I think should be at a retrospective. Food. The simple act of having food around relaxes the team. It invites discussion. Some Scrum Masters prefer to play icebreaker games. Me, I find that just having the food around helps.

One last note: a retrospective is only useful if the actions brought up during the retrospective are actually acted upon. If they are not, and they just get noted down and filed away, then the meeting itself becomes useless. It is through the actions being implemented that the team improves, and if you do it continuously (Kaizen) your team only keeps getting better.