This is the second chapter. Lets see how we go.

The Agile Mindset

There are two parts to being Agile. The first half is the Agile mindset. This is where your thinking needs to change. Agile when implemented correctly is a paradigm shift in the thought process compared to how work is performed today.

The second half is the process. The process adds discipline and structure to your Agile thinking. Implementing the Agile mindset, is a cultural change. Even if you do not implement the process side, you can still do great things. The problem is that most people, when they start to implement Agile only implement the process. Although benefits can be gained, they are small. The process itself feels empty like you are just going through the motions, which you are. If you don’t make the leap to the mind set, then most likely your Agile journey will end and you will regress back to your previous work practices.

So what is the Agile mindset and what is the alternative mindset?

According to Linda Rising and her talk on the Agile Mindset, there are 2 types of people. The first is people that think you are born with a certain level of intelligence/talent or ability, you can learn new things, but you can’t change how intelligent/talented or able you are.

The second type of people are those that think that no matter how intelligent /talented or abled you are, you can always get better. Sometimes you can improve a lot.

The first type of people are considered the “Fixed” mindset. The second are considered the “Agile” or “Growth” mindset. Now, we all have these mindsets at some point. We flip flop depending on the situation and what we know all the time, but some people are more dominant in one mindset that the other.

People with the fixed mindset are more prone to fear failure. They will choose an easier path. The path of less resistance. The one less prone to failure.

Their thinking is that it is too difficult to do, so why try. They avoid challenge and prefer proven techniques. Techniques that have proved their success. Alternatively, when they fail, they look at the “success” in the failure and focus on that. These people are more interested in looking good.

On the other hand, those with the Growth or Agile mindset, look at a difficult situation and think – If I just work a little longer, try a bit harder, spend a bit more time on it, I will get it. If they fail, they try again.

There have been numerous psychological studies on this. In one of these studies, it found that a particular mindset can be easily induced. At least for a short period. Ever been told that something is too difficult to do, then give up? Alternatively, when you do something well, you think I’ve made it. Then stop? That is the fixed mindset.

On the other hand, if you have been told that something is too difficult and decided to try it for yourself anyway, or when you get something right, try to improve it, that is the Agile mindset. These are just a couple of examples.

The thing is that we become either mindset when we are young. If we are told when we are children that we are “Talented” in something or “You’re so smart!” or the negative “You are so stupid” or “You won’t amount to anything”, then this induces the expectation. For those that get the praise, they become praise junkies. They look to what they can do to keep getting the “You’re so talented” praise. The best way to do that is to find a challenge that isn’t too difficult. One that isn’t too far out of reach.

The problem is, that when a child with this type of thinking comes across a challenge that is too difficult, the child either avoids or ignores the challenge.

These are the children that grow up to be fixed mind set dominant.

Alternatively, children that are praised on their “effort” rather than that result, even if they fail, or for the negative, told that they “need to work harder” actually become more resilient to change. They try to tackle it head on. They are more open to ideas and willing to give them a go, because failure is part of life and you just move on.

These children grow up to have an Agile dominant mindset.

Its not only people that can have these types of mindsets. Organizations can too. It is not surprising. Organizations are made up of people.

But, all is not lost. People can change. Those with a fixed mindset can have an Agile mindset. You just need to want it.

So with Agile development in mind, the Agile mindset at its core is:

- Thinking of your customer first. How can you make their life easier/better or what value can you give.

- The willingness to try and learn new things.

- Have the goal to improve yourself, your team and your colleagues and

- Never be afraid to fail.

Thinking Of Your Customer

When I say “Thinking Of Your Customer” the question that comes to mind is “Who is your customer?”. The first and obvious answer is the people who use the product or service that you provide. These may be the general public or other companies. By thinking of the customer in this instance, you try to provide a product that is valuable to them. Value can be very subjective. It could be something simple that helps your customer accomplish a goal or it could be a complex.

For example, Facebook started out as a web site where University students (I’m Australian so I won’t say College – A College here is high school) stay in contact and share information. Google started out as a search engine because the founders didn’t like the current search engines that were out there. They thought that a good search engine would be valuable to others. Zappos wanted to see if people wanted to buy shoes online.

These companies started by adding large amounts of value to a small group of people. It wasn’t until later that they stared expanding and adding value for other customers.

The second lot of customers are your internal customers. These are other teams or other members within your team. Be they under you, your peers or your seniors. These customers, you help indirectly. For the people under you, there is the concept of “Servant Leadership”. Servant leadership is much different to the standard method of leadership which I will term “Command And Control”. With Servant Leadership, instead of telling people what to do as you would with Command and Control leadership, your job is to guide and grow your people. Give them direction and hen get out of their way.

You, as the leader have the big picture. So you give the team the goal to help accomplish the big picture. You do not tell them how to reach the goal, you leave it up to the team. If the team veers too far from the goal, you nudge them back toward the goal. You never ever tell them how to reach the goal. The reason for this is that it helps grow your team. The team becomes stronger because they make mistakes (and they will) but you guide them back. You never solve the problems for them, you need to let them solve the problems them self. Believe it or not, this makes for a happier team as the members then have full responsibility for reaching the goal. The autonomy to make decisions on how to reach the goal themselves. They also master the skills required to accomplish the goal. For those that are peers, you help make their jobs easier. Try not to send crap work. Share knowledge. For your manager, help them accomplish their goal.

By thinking of the people first instead of results, you grow your customer base, both externally meaning more profit, and internally meaning you have a more dedicated workforce.

One thing to remember though is that respect for one another can be gained very easily. It can also be lost very easily. The problem is that once it is lost, it can be very difficult to regain.

The Willingness To Try And Learn New Things

By simply having an open mind to try something new. By trying something new, you open your mind to new possibilities. A way to work better. A way to work faster. A way to improve quality. As humans, we try to find the one true or best solution. For some problems, this is the case.

These types of problems though in reality tend to be the simple problems. What font size is the best for me to read. What is the boiling point of water at sea level. These are like “Mount Fuji” type problems where the peak is the optimal solution.

photo credit: reggiepen Reaching Out via photopin (license)

For more complex type of problems, the landscape is a little different. There are peaks and valleys. One solution is at a peak, the dismal failure is in the valley. The problem is that there are many peaks. Some higher than others. The only way to reach another peak is via a different path.

These types of landscapes are like a “mountain range”. The only way to find out which peaks are the highest is to try different things. Different combinations or completely methods altogether. Even counter intuitive methods can bring surprising results.

photo credit: romanboed Sunny Mont Blanc via photopin (license)

For really complex problems. More like real life problems. We have the mountain range, but it shifts continuously. In other words, its waves. You may be high at one point, but if you stay still long enough, or short enough, you are in the valley of failure. The only way to continually remain high is to “surf” the waves. You have to continuously shift and change. What worked one day will not necessarily work the next.

photo credit: jijake1977 Rip Curl via photopin (license)

Companies like Google continuously try new things. They have great successes, Their search engine, Gmail but they also have dismal failures. Google Wave, Google+. Yet they continuously surf.

Peter Palchinsky a Russian engineer in the early 20th century summarized how to surf through his 3 principles.

- Seek out new ideas and try new things.

- When trying something new do it at a scale that is survivable.

- Seek Feedback and learn from your mistakes.

This leads us to our next section.

Continuous Improvement

Continues Improvement as the name suggests is well, improving continuously. Not every now and then. Not when you have the time. But always. Always looking for ways to improve. This on itself is hard. Paul Akers from 2 second Lean suggests everyone looking for an improvement of 2 seconds every day. His findings are that if everyone looks for improvements of at least 2 seconds, then every now and then, a significant improvement is found. Even if it doesn’t. Those little improvements build up over time. This in Lean terms is called Kaizen.

So instead of thinking “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” think “If it ain’t broke, fix it anyway”.

So the question now becomes, how do you improve? What is the definition of “improvement”. Well, its different for everyone, but for me and what I think it is in Agile is simplification. Simplify the process, simplify the program, simplify as much as you can. The best way I think to simplify something, is to subtract the complexity.

Waste

In Lean, the simplification process is done through the removal of what they call Waste. There are 3 major types of waste in Lean.

- Muri – The waste of Overburden.

- Mura – The waste of Unevenness and finally

- Muda – The waste of Futility.

These wastes are further broken down into 8 more wastes.

- Overproduction – This occurs when you create more than you currently need. When you over produce, you need to store the over produced product. This becomes

- Inventory – Then you need to figure out how to move all your stock. This leads to

- Transport where goods are moved from one area of the warehouse to another. Then you have to work out a process to keep track of everything. This is

- Over processing. Your processes become more complex. Stock gets damaged. The damaged stock become

- Defects. To fix the defects, your people need to move the stock back onto the floor, fix the defect then move it back into storage. This is a lot of

- Motion. All the while, your customers are

- Waiting for their goods. All the while your people are sick of redoing work. They want make things better, they want to be happy at work. But they can’t because they are not allowed to. They fell they have

- Underutilized talent.

Notice how I put the 8 wastes into a story I have taken this queue from Paul Akers of 2 Second Lea. The idea being is that having a little story you can tell about the wastes. It helps you learn them, but also helps you understand them. its much better than just remembering an Acronym such as DOWNTIME.

Now these wastes are generally for the Manufacturing industry, but they are similar to what you will see in the IT space. Saying that, there is a list of wastes specifically for IT. I’m going to attempt a story here, but I don’t think it will be as good at the one above.

When you have so much work to be done, and its all done on the fly with no

- Standards and Manual work, the priority of tasks keep changing. Do this now, no stop that and do this. You are constantly

- Task Switching. This leads to

- Partiality Done Work. Nothing really gets completed on time. Everything gets late. the customer is

- Waiting for their software longer. Since it takes so long to get to the customer, and we are under the pump, we make mistakes, cut corners this introduces

- Defects that need to be fixed. The buggy code goes back to development, then testing, then UAT again. Its constantly in

- Motion. The software is so buggy, we introduce gated changes and procedures and other.

- Extra Processess to prevent the issues.

The deadline looms, Nothing is complete. Everyone stays back late into the night. Works weekends. Their

-> Heroics is astounding.

We finally ship. We planned everything up front, Did everything the customer initially specified. Oh no, they didn’t really need that- Extra Feature that we spent months building. It has no business value. It was just a nice to have.

Believe it or not, but over 90% of the work you do is waste of some sort or another. I know, it’s an outlandish statement, but this is part of the mindset. The hard bit is trying to remove that 90%. Most of the stuff we do we think is required. That is why we do it. But if you really really look at it, there are ways we can automate, remove or change our practice to reduce. Over time, you will find that you are doing the same amount of work quicker. In most cases significantly quicker. You will also find that you can do more in the same amount of time as you do one thing now.

It is through the reduction and or removal of these wastes which is at the heart of Agile. It is one of the methods on how you get faster. What? You thought that doing Stand-Ups, Sprints and so forth would make you faster? How would it? you are adding extra processes (a form of waste) if you apply it to the way you currently work without changing the way you work. You are actually making things longer. Just think about it.

Feedback loops

The other tool to help with Continuous Improvment is the Feedback loop.

This is a universal tool to improve. There are many feedback loops. I mentioned one earlier. Peter Palchinsky’s principles.

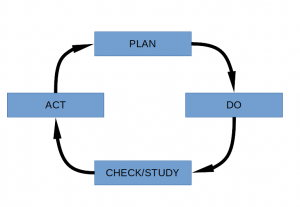

Another one that is synonymous with Lean is the Demming Cycle, or the PDSA/PDCA loop which stands for Plan, Do, Check/Study and Act.

You

Plan what you are going to do.

Do what you are going to do.

Check or Study the results from what you have done.

Act on the results of that Check or Study and feed that back into the next Plan.

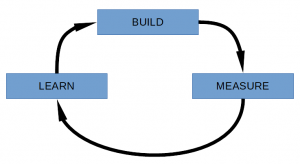

Another type of feedback loop created by Eric Ries of Lean Startup is the Build, Measure, Learn loop.

You Build a piece of the product. Just enough to get a minimum working product.

Release to your customers.

Measure their responses to that minimum viable product.

Learn based on the measurements what the next direction will be, then Build the next iteration. Do this continuously.

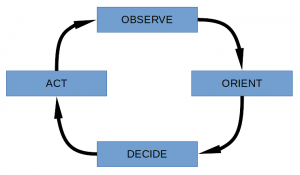

Yet another feedback look is the Observe, Orient, Decide, Act.

Observe the situation.

Orient yourself based on the observation.

Decide What to do.

Act Then do it.

In Scrum, there is a feedback loop within a feedback loop. I will go through that in more detail when I cover Agile methods. Especially Scrum.

Now, there is no sure way you can eliminate waste, adding feedback loops and short cycles will help, but ultimately this is a trial and error process. The problem with trial and error, is that you have to be able to accept error. In other words, failure.

Not Being Afraid To Fail

The fear of failure is generally what holds people and companies back. They become cautious, slow down. Take the easy route. If you fail, you are seen as a pariah. Failure is stigmatized so it is avoided at all costs. Eventually you stagnate.

People and companies that embrace failure, look at it as a learning experience actually become more healthy. They learn and grow. Some companies actually embrace failure. For example, at Etsy, the person who broke the build the most times at the end of the year is awarded a 3 armed sweater. Other companies hold a celebration. The failure is celebrated as a learning experience. It is investigated and ways are found to prevent the failure from happening again in the future.

Yes you may fail again, but so what. It’s part of learning.

Those of us who are in senior roles, why are you there? Is it because you got everything right? How did you get it right? Or Is it built on a lifetime of failures where you learned?

Further along, I’ll go through a game you can play to help remove the stigma of failure from your team.

It is my belief, and thats all it can be as I’m not a psychologist or expert on human behavior, that by taking these 4 core principles of Thinking of your customer (people), Having a willingness to try new thing, continuously try to improve and finally not being afraid to fail, will give you the required foundation to have an Agile mindset.

If you find it hard to have this mindset, and it will be difficult to change, my advice is “Fake it till you make it”. The mere fact that you are trying to change will help you to change.